Starting off the new year with a new citizen.science post!

Has it ever crossed your mind that part of genetic genealogy is a little bit like The Big Bang Theory?

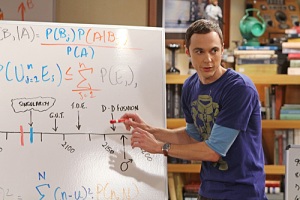

Those who watch the TV show will have noticed that Leonard conducts hands-on experiments in a lab, whereas Sheldon’s work appears to consist of writing formulas on a white board and pondering them. Leonard is an empirical scientist, dealing with real, observable results. Sheldon is a theoretical physicist—in genetic genealogy, that might be akin to proposing theories based on calculations and simulations.

Image 1. Leonard with Penny (source)

Image 2. Sheldon (source)

Leonard and his buddies conduct experiments for fun too, for example bouncing signals around the world just to turn on a lamp. We genealogists can also play at being scientists, collecting real data and developing hypotheses to support or enhance or challenge the expectations produced by pure math and simulations.

Here are just three of the many questions that citizen scientists in genetic genealogy can explore with our match data.

- How much DNA do two 4th cousins share?

- If two people share just one matching DNA segment between 7 and 8 cM, how likely is it that this segment was passed down from a common ancestor and not a false match, perhaps resulting from a genotyping error?

- If two people share a large-ish matching DNA segment (say, 40 centiMorgans or more in one segment), could that be another factor in predicting how closely two people are related?

Blaine Bettinger addressed Question 1 in his invaluable Shared Centimorgan Project. He used crowd-sourcing to collect data on over 10,000 pairs of confirmed relatives. The result is a chart showing the common ranges of shared DNA for each degree of kinship, available on the ISOGGWiki here. Simple math tells us that two 4th cousins may share an average of 13.28 cM, but Blaine’s study found the range anywhere from 0 to 90 cM.

It’s not too late for us to participate in this ongoing study. See details on Blaine’s blog here.

In a conversation in the comments to those posts, Blaine noted “… how little we really know and how much more study is needed. We need SO MANY other citizen science projects like this one to analyze data.”

That’s what citizen science is. People like us, mostly without degrees in science, asking questions and gathering data from real subjects and analyzing and discussing the results.

Some of us have used just our own immediate family to explore Question 2, above. What threshold should we use to decide a match is too small to be worth our time? I posted the results of my study in July 2016 here. Blaine recently shared his own here. You need a trio of a child and two parents (in my case, my son Dan and his parents) to test; then look for people who match the child but neither parent, suggesting a possible glitch in the matching process and not a real match. In my case, using AncestryDNA data, each of Dan’s matches over 15.5 cM matched one of the parents too, and more than 95% of the matches over 10 cM did as well. I consider those fairly reliable. But a quarter of the matches from 7-10 cM matched Dan but matched neither parent. From this study, I’ve decided not to spend time on those without other incentives.

We can all create our own humble citizen scientist projects. Right now, I’m working on Question 3, limited to my own immediate family data, exploring this question:

What are the odds that two people with a matching segment of 40cM or more are likely to be 4th cousins or closer?

Stay tuned for answers in my blog in a future post.

Ann Raymont (c) 2017